Government response

The purpose of this section is not to provide an exhaustive history of adaptation in South Australia, but rather to provide an adaptation’ snapshot’, and a ‘quick critique’. The documents hyperlinked to this report provide the greater context for understanding adaptation progress so far.

Early coastal climate adaptation legacies

The first legacy came from the early surveyors in South Australia who reserved much of the coastline for public use, and despite some loss from erosion, the majority of these reserves remain today. This practice reflected an early perspective in South Australia that the beach and foreshore belonged to the community and in most places this planning practice included the provision of an esplanade road. However, often the esplanade road and associated development was placed too close to the shoreline and sometimes within the dune system itself.

This practice also means that local councils who own the esplanades are on the forefront of coastal adaptation and private assets situated behind these roads are afforded de facto protection. The adaptation question in South Australia is more often: 'How long the council can protect its esplanade?’ and not, ‘How long before private assets are impacted?’.

Exceptions to the ‘esplanade rule’ include holiday shack settlements that sprung up in the 1940s to 1960s which often saw development placed adjacent the beach with no esplanade road.

The second legacy came after a series of storm events that occurred along the metropolitan coastline in the 1950s and 1960s. The resulting damage to infrastructure and coastline led to the formation of the Coast Protection Board in 1972. The Board’s coastal policy was formally adopted as South Australian government policy in May 1991. Based on the First Assessment Report of the IPCC, this policy was the first of its kind in Australia and in 1993 sea-level-rise benchmarks were implemented into the SA planning system.

1953 Dune erosion, Brighton Beach. Source: SA Water

1953 Dune erosion, Brighton Beach. Source: SA Water

That only 5 dwellings had water over floor levels in Gulf St Vincent in the major event of May 2016 can be attributed in part to these early practices and policy interventions.

Other legacies from this era include:

- A policy of not providing public funds for private protection unless there was clear community benefit in doing so.

- Beach profile survey data that dates back in some locations into the 1970s. However, analysis of the implications of the modelling is not well known.

- The allocation of 1-in-100 ARI storm surge allowances for settlements around the state to ensure that new development was appropriately positioned.

- Historical aerial photography, often taken by personnel leaning out of the windows of light aircraft.

Regional climate change adaptation responses (2010–16)

A Climate Change Adaptation Framework for South Australia (pp 33–34) was adopted by the state government in 2012. In summary, the adaptation framework found its genesis:

- From powers granted within the Climate Change and Greenhouse Emissions Reduction Act 2007 to form regional partnerships with governments, businesses, and peak bodies.

- From the formation 12 government regions, with these given further impetus in the 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide in 2011.

- In the recognition that the economic, social and environmental impacts of climate change will vary across South Australia and a regional approach to adaptation planning was preferred.

- In 2011 the Local Government of SA (LGA), developed the first climate change adaptation guidelines to support the development of regional climate adaptation plans (in partnership with the Central Local Government Association, DEW, NRMs and RDAs).

The framework design was such that each government region would work in partnership with varying levels of government and their agencies, community groups, peak bodies and business interests to first conduct an integrated vulnerability assessment, and then a regional climate change adaptation plan. All 12 regions completed adaptation planning by the close of 2016.

For more information on the regional adaptation planning process.

Quick critique

Having extensively reviewed all of the regional adaptation plans in relation to coastal adaptation matters, and having consulted with various local councils the following critique is offered5:

- The general consensus from coastal councils is that the adaptation process had positive outcomes in bringing climate change adaptation into focus.

- Adaptation plans made recommendations that digital elevation models should be acquired and ongoing monitoring take place in coastal zones.

- Data collected in the Integrated Vulnerability Assessments was qualitative in nature, relying on expert opinion ‘in the room’.

- The process tended to produce generalised findings and recommendations over a broad coastal region, rather than specific localised adaptation strategies.

- The general anecdotal feedback from councils is that the regional adaptation planning did not provide a framework for ongoing coastal adaptation work.

In the light of adaptation management issue 1, this is not an unsurprising finding. A regional approach to coastal adaptation is not capable of dealing in a fine-grained manner with specific coastal localities.

5 Note: the author completed a critique of all of the Regional Adaptation Plans for the LGA in 2017 as part of an internal review of the process. The report to the LGA is available on request.

Take-away summary: Regional adaptation planning qualitatively assessed vulnerabilities to climate change in the coastal zone and produced regional adaptation responses.

Natural resource management (2010–16)

Natural resource management in its current form finds its genesis in the passing of the Natural Resources Management Act 2004 that introduced a new system of integrated and regionalised action. The Act also establishes regional NRM Boards to give ownership and responsibility for NRM to regional communities.

Significant progress has been made in the management of natural resources since 2010:

- The EPA has undertaken 390 aquatic ecosystem condition assessments at 289 nearshore marine sites.

- DEW, in partnership with the NRM Boards, has prepared coastal conservation assessments for mainland coastal areas. These assessments have consolidated existing data providing a baseline to update in future as required.

- DEW has consolidated detailed baseline reports for 19 marine parks.

Various NRM plans since 2006 and the State of the Environment Report 2008 formed the practice of reporting on trends within various ecological features. These trend reports in their latest form are presented as easy to read ‘report cards'.

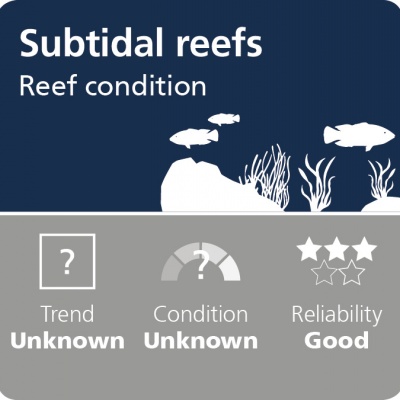

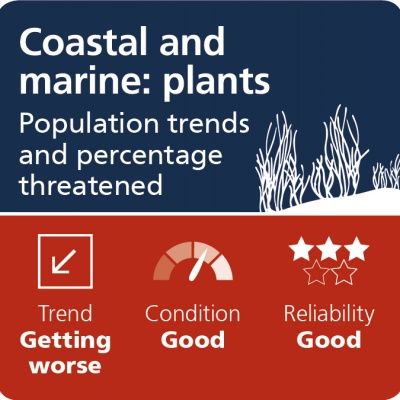

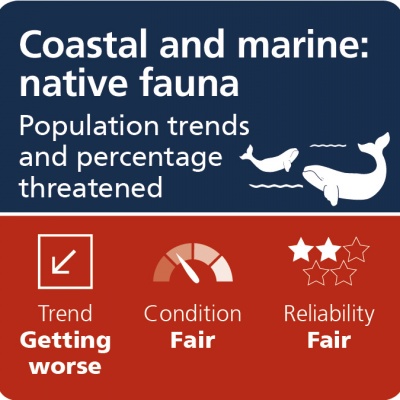

Figure CP8: Trend and condition reports for coast and marine in South Australia

Quick critique

- Significant work has gone into identifying baseline studies for various marine and inter-tidal environments.

- A simple ‘report card’ mechanism has been employed to communicate the trend in various sectors.

- The general trend is one of stability and improvement in contrast to earlier reports of 2006 and 2012 (NRM).

- Baseline studies will assist in monitoring the impacts of climate change over time.

Take-away summary: Natural resource management work has created baseline studies within various ecological sectors from which to monitor change over time.

Adaptation of urban settlements (2010–16)

The Coast Protection Board (CPB) produces policy that is adopted as South Australian government policy.

The Board’s Strategic Plan for the 5 years from 2012–17 identified 3 strategic priorities:

- Adaptation of existing development to coastal hazards and the impacts of climate change.

- Ensure new development is not at risk from current and future hazards.

- Plan for resilience in coastal ecosystems to adapt to the impacts of climate change6.

6 Review note: generally there is a division of labour between NRM (that has monitored natural environment) and CPB (which has worked within urban settlements). While CPB maintains this strategic priority in practice it appears less focused (as evidenced in 2016–17 report that showed no expenditure for work within ecosystems).

The works undertaken to fulfil these objectives include the following:

- The CPB works with local councils to identify areas at risk and to develop mitigation strategies and will provide grants for up to 80% of the total cost of studies and works.

- The CPB administers the Adelaide Living Beaches strategy which ensures that sand supply is maintained along the metropolitan beaches.

- Policies, including those dealing with climate change hazards, have been integrated into the general section of all Development Plans across the state. The CPB also seeks to ensure that coastal zones are established over sensitive coastal areas.

- Development Applications identified in Schedule 8 of the Development Regulations 2008 are required to be referred to the CPB (in reality Coastal Management Branch) for either advice or direction.

- Beach profiles have been surveyed around the state since the 1970s.

The way in which the CPB has historically interacted with the planning system is illustrated below.

Figure 9: The Coastal Protection Board and the planning system

Figure 9: The Coastal Protection Board and the planning system

Progress in specific adaptation projects include:

- Fine-grained local coastal adaptation studies have been concluded for coastal settlements in the Adelaide Plains region, some settlements on Yorke Peninsula, and Southend near Beachport. Coastal adaptation studies currently underway include Kangaroo Island, Alexandrina, Marion and Onkaparinga councils.

- Progress has recently been made in the collection of LiDAR data. Consultation with DEW suggests that most of the SA coastline will have been captured digitally in the last 3 years with the exception of Yorke Peninsula (that does have significant numbers of settlements captured), and the southern tip of Fleurieu Peninsula from Sellicks Beach to Victor Harbor.

- The implementation of protection works has also proceeded in various locations around the state. Since the storms of 2016, there have also been projects instigated by private landholders who have funded their own projects while under supervision of Coastal Management Branch.

The CPB position paper produced in May 2015 identified 5 coastal management issues that it considers represent significant risks to the South Australian community and environment:

- Applications from councils for CPB grant funding for projects to address coastal hazards exceed the Board’s available budget each year. High priority risks remain unaddressed. Typically, the Board has between $350,000 and $500,000 per annum available for grant funding to council projects.

- Integrated coastal protection and adaptation plans are required at a number of regional settlements along the South Australian coastline.The Board currently has limited capacity to provide funding support for these projects.

- Sand needs to be added to Adelaide’s beaches to offset the effects of sea level rise. Resources are not currently available for the required investigation of potential sources, or to fund the addition of sand to the beaches.

- Resources are not available to assess the current condition and maintenance/asset renewal requirements of the ageing seawalls on Adelaide’s coast, or to commence investigations into the need, feasibility and design parameters for an offshore breakwater at West Beach.

- Despite the Board’s legislated role in the development assessment process, some coastal development continues to be approved against the Board’s advice. From 2004–13, 276 dwellings and 126 extra allotments have been approved ‘at odds with the Board’s advice regarding coastal hazards’.

Quick critique

- The integration of the CPB policy into the planning system has ensured that most new development since 1993 has been implemented with a consideration of sea level rise risk.

- The Board seeks to facilitate adaptation planning and protection works but is severely under-resourced to do this effectively. As sea level continues to rise, it is likely that the funding gap will continue to widen, and costs continue to rise due to the inability to act in a timely fashion to the threat

- Despite having a legislated role in the development assessment process, some development continues to be approved against advice.

Take-away summary: Adaptation planning is proceeding slowly, and coast protection in urban towns and settlements is severely under-resourced.

Summary critique of coastal adaptation progress

Significant progress has been made since the introduction of Prospering in a changing climate: a climate change adaptation framework for South Australia. The 2017 plan, Towards a resilient state: South Australian Government’s climate change adaptation action plan seeks to build upon this progress and outlines 65 specific actions across various government and community sectors.

Legislative

The Climate Change and Greenhouse Emissions Reduction Act 2007 has provided the necessary flexibility to create partnerships and agreements to facilitate coastal adaptation.

Regional adaptation planning

Climate adaptation response has been centred in regional climate change adaptation plans (all finalised in 2016). The plans recommended that digital elevation models be captured and that monitoring programs be implemented.

Anecdotal feedback from local councils suggests that regional adaption plans have not provided any real direction in how to conduct coastal adaptation within their localities.

The current adaptation plan (2017) tends to emphasise ongoing regional planning (actions 35–38).

Natural resource management

Significant effort has gone into mapping and creating baselines in marine and inter-tidal zones from which to monitor future changes (report cards). Many programs and plans have made significant improvements in water and environmental management.

The current adaptation plan (2017) maintains an emphasis on natural resource management in the context of climate change (actions 12–17)

Urban cities, towns and settlements

Early implementation of coastal policy in planning controls has seen most development implemented subsequent to 1993 taking into account sea level rise benchmarks and associated coastal hazards.

However, on a smaller scale some councils are approving development contrary to advice or Development Plan policy. This would suggest that planning controls need to be strengthened for proposals in coastal areas.

Progress has been made in the collection of digital baselines over the last 3 years, but this has been mostly driven from councils and regions, rather than a coordinated approach from the state government.

Coastal protection work continues, but is severely under-resourced to meet the challenges.

Monitoring and data collection

The removal of the SEAFRAME gauge from Port Stanvac in 2010 means that 8 years of key sea level rise data has been lost.

The current adaptation plan (2017) places an emphasis on ‘monitoring the plan’ but little emphasis on the collection and monitoring of data.

1900 Seacliff looking north to Brighton jetty. Source: Department for Environment and Water

1900 Seacliff looking north to Brighton jetty. Source: Department for Environment and Water 1953 Dune erosion, Brighton Beach. Source: SA Water

1953 Dune erosion, Brighton Beach. Source: SA Water

Figure CP7: Regional model for developing adaptation responses. Source:

Figure CP7: Regional model for developing adaptation responses. Source:

Figure 9: The Coastal Protection Board and the planning system

Figure 9: The Coastal Protection Board and the planning system